WHAT IF APOLLO NEVER DIED? Part 1: One Has To Wonder...

I find myself in the mood to write. In order to flex my writing muscles, if you will, I decided to engage in a bit of speculation, to whit, the title of this article.

Make no mistake, Apollo didn't just die, it was killed. There were many factors contributing to this: the Vietnam War, lack of both government and public interest, political interference. As President Lyndon B. Johnson, the space program's biggest supporter, colorfully put it, it was all "pissed away."

Again, make no mistake, figuratively and literally demolishing the Apollo infrastructure and systems in favor of the built-from-the-ground-up/wholly-new Space Shuttle was extremely costly in both money and knowledge.

In our history, Apollo moon missions ended after only six landings in December 1972 with Apollo 17. Of those landing only three of them had truly begun to scratch the surface of what was on the Moon. The program then gave its last big gasp with Skylab, launched in 1973. The interim space station hosted three crews and actually did accomplish a great many feats of research, endurance and observation. Finally, things sputtered to a close with the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975. No American astronauts would go into space again until the Space Shuttle was finally launched in April 1981.

The Shuttle had a hard life, don't get me wrong. It's purpose was continually redefined over the course of its development and career and inherent frailties were exposed tragically with the loss of Challenger and Columbia. When it finally came to time to build the massive space base that NASA had been jockeying for since the late 60s, it came at the prices of being reliant on international cooperation and having to use launch vehicles that would take many, many trips to fully assemble the station. And now, almost 10 years after the station was finally completed, they're talking about de-orbiting it in the early 2020s. And with the Shuttle program ended in 2011, we now wait to see if NASA can get back on the horse, as it were, or will have to become utterly dependent, some would say subservient, to private enterprise for human spaceflight.

But what if things went a little bit differently? What if the government and the American people had chosen to squeeze the $24 billion Apollo investment for all it was worth?

In my mind, at least three things would have to change to guarantee Apollo to continue. These are pretty big historical fudges, I'll grant, but since the very nature of this is speculation, we might as well go all out.

1. The Vietnam War either doesn't happen or is a much smaller conflict that the US is able to exit from without massive civilian ire and/or drain on taxes.

2. Nixon does not become President in 1968.

3. NASA does a MUCH better job on its PR.

Admittedly, the fudge-iest one of the three is Nixon. I do feel that he needs to be removed from the equation as much as possible however, as he was not terribly interested in the space program, insomuch as it could be a tool for personal prestige. At least Kennedy, with his doubts, felt it should be a tool for national prestige. But as I said, this is speculative anyway, so we'll just say that for this timeline scenario, Johnson runs for a second term and actually does manage to defeat Nixon by a very, VERY slim margin. In fact it goes down as the absolute closest election in US history. As for Vietnam, as much as I would like to spare the soldiers from that hell, it's more than likely it would still occur no matter what in any realistic setting. Keeping it small is probably the most likely of outcomes. I say all this though without saying that I am an expert on history or politics so bear with me.

Now that the stage is set, we enter the Apollo program as it begins in 1967...

1967-1968

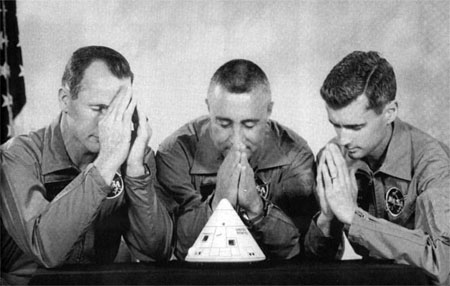

Apollo 1 was to launch in February 1967 to test the brand-new Apollo CSM (Command/Service Module). The crew was, however, tragically killed in a fire on the launch pad during a launch dress rehearsal. Manned missions would stop for about 20 months while the spacecraft was rebuilt. Testing of the Lunar Module (LM) and the Saturn V rocket would continue. Just to add a bit of a twist to our alternate history speculating, while NASA did cancel the next two flights that would have been Apollo 2 and 3, they then shuffled those numbers forward to the missions that did fly. Thus we get Apollo 4, first flight of the operational Saturn V rocket, becoming Apollo 2 and etc. The remaining schedule would follow history much as it did.

NASA also used an alphanumeric code system to classify the different Apollo missions

A missions would test the Saturn V

B missions would test the unmanned LM in Earth orbit

C mission would be manned test flights of the CSM

D missions would test the complete spacecraft stack in Earth orbit

E missions would test the CSM/LM combination in a high. elliptical Earth orbit

F missions would be the dress rehearsal for the first landing

G mission would be the first landing attempt (possibly multiple attempts if Apollo 11 had crashed)

After the first landing was accomplished, additional mission types were added.

H missions would be extended stays on the lunar surface of up to 2 days

I missions would be lunar observation from orbit

J missions would be extended stays of up to 3 days on the Moon with an instrument bay in the orbiting CSM and the moonwalkers using the Lunar Rover on the surface.

In our history only the A, B, C, D, F, G, H and J missions were flown. In this alternate timeline, it would go something like this.

Apollo 2 (A1) is the first test launch of the Saturn V (vehicle AS-501) on November 9, 1967

Apollo 3 (B1) is the unmanned test mission of the LM on January 22-23, 1968, using the AS-204 Saturn IB rocket originally meant for Apollo 1

Apollo 4 (A2) is the second test launch of the Saturn V (AS-502) on April 4, 1968. It suffers several major glitches but these are able to be corrected in order to man-rate the Saturn V

Apollo 5, launched in October 1968 on the SA-205 Saturn IB, tests the new CSM in LEO (low Earth orbit) for ten days. The crew is Mercury veteran Wally Schirra and rookies Don Eisle and Walt Cunningham. However, due to certain complications with the crew, especially in the wake of the Apollo 1 fire, NASA management quietly makes sure that none of three ever fly again.

Apollo 6 is launched in December 1968 as the C Prime mission on the AS-503 booster. Due to fears that a recently discovered Soviet superbooster (in reality the N1-L3 rocket) would get cosmonauts to the Moon before the US did, the CSM is launched to and orbits the Moon with the crew of Frank Borman, Jim Lovell and Bill Anders.

1969

Apollo 7 (D/E1) is launched on Saturn V AS-504 in March, 1969. After reaching initial orbit, they fire their S-IVB third stage and fly an elliptical Earth orbit with an apogee of 4,000 miles and perigee of 150 miles to test the complete CSM/LM combination. Crew was Jim McDivitt, Dave Scott and Rusty Schweickart. During this mission, NASA revived the concept of naming the spacecraft, which had been abandoned in the Gemini program (with the exception of Gus Grissom's name for Gemini 3, the "unsinkable" Molly Brown). They named the CSM Gumdrop and the LM Spider.

Apollo 8 (F1) launches in May on the AS-505 booster, aiming to test the CSM and LM in lunar orbit and mock descent. The crew of Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan put Charlie Brown and Snoopy through their lunar paces.

Apollo 9 (G1) makes the first landing in July 1969, fulfilling Kennedy's deadline. AS-506 delivers the Columbia and Eagle to the moon where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin become the first astronauts to walk on its surface... but only for two hours.

Apollo 10 (H1) duplicates this attempt but stays for slightly longer. AS-507 boosts Yankee Clipper and Intrepid to the Ocean of Storms where Pete Conrad and Al Bean land Intrepid within 600 feet of the derelict Surveyor 3 probe

1970-1971

Apollo 11 (H2) is intended to use the AS-508 booster to place Odyssey and Aquarius on course to the Moon with crew of Jim Lovell, Jack Swigert and Fred Haise. However, an explosion in an oxygen tank on April 13, 1970 cripples their spacecraft and, well, you know the rest.

Now we start entering the realm of the truly speculative. Apollo had already begun to feel the budget office scythe before Neil Armstrong even made his famous quote. The request for more Saturn V rockets was denied in 1968 and by 1970 the production lines were completely shut down. Not so here. In fact it is in this year of our fictional timeline that the first of the new lot of Saturn V rockets, AS-516, starts production. Also, with more funding and with the PR department playing up the heroism of astronauts and mission controllers in saving Apollo 11 from complete disaster, there isn't as much pressure to stretch out time between missions.

Apollo 12 (H3) resumes moon missions on January 31, 1971. Crew is Alan Shepard, Stu Roosa and Ed Mitchell and spacecraft are Kitty Hawk and Antares.

Apollo 13 (H4) blasts off on the AS-510 booster June 6, 1971 with crew of Dave Scott, Al Worden and Jim Irwin. Crew named their spacecraft Endeavour and Falcon. This mission continues to be an H-class mission because in this timeline, NASA boss Thomas Paine does not engage in an ill-advised attempt at trading with the Nixon White House.

Apollo 14 (J1) is the most ambitious mission yet. Launched on October 31, 1971, the AS-511 booster sends Casper and Orion with crew of John Young, Ken Mattingly and Charlie Duke on a three-day stay at the Moon with Mattingly operating a Scientific Instrument Bay in the Service Module and Young and Duke driving the Lunar Rover on the surface for the first time.

1972

Apollo 15 (J2) is launched by the AS-512 booster on March 6, 1972, the program's first night launch. Spacecraft America and Challenger, with crew of Gene Cernan, Ron Evans and Joe Engle conduct a three day mission tot he Taurus-Littrow Valley, one of the most spectacular sites on the Moon so far.

Now things begin to change even more...

Without heavy cutbacks, President Johnson still supporting, and more public support in general (and even some in Congress!), the Apollo Application Program moves ahead. More Saturn Vs are being built and the Skylab space station moves forward faster than it did originally.

On May 14, 1972 (exactly one year earlier than it was originally launched) Skylab (SL1) is lofted into orbit by the AS-513 Saturn V, the third stage of which had been converted into the Orbital Workshop. But in a case of the number 13 perhaps biting NASA in the hindquarters again, the station is damaged on ascent and the Skylab 2 crew (SL2), launched on the SA-206 rocket, had to effect ad-hoc repairs. They then stayed for 28 days, the longest a US crew had been in space to that point. The only difference with the real-life Skylab is that this version launched without the Apollo Telescope Mount, which had been created out of a LM that never flew to the Moon.

On July 4, 1972, Apollo 16 (J3) created spectacular Fourth of July fireworks in the program's second night launch. The AS-514 booster propelled the spacecraft Independence and Liberty to the Moon with crew of Dick Gordon, Vance Brand and Dr. Harrison 'Jack' Schmitt. Gordon and Schmitt's mission was ambitious. In addition to the fact that Schmitt would be the first professional scientist/geologist to walk on the moon, their target was the Tycho crater, one of the brightest on the Moon and also the landing sight of the Surveyor 7 probe. They spent three days exploring the rim of the crater before returning to their CSM in orbit.

Later that month, the Skylab 3 mission (SL3) has an astronaut crew stay for twice as long on the station, a total of 58 days, breaking yet another record.

The last Skylab mission (SL4) was lofted by Saturn IB SA-208 on November 16, 1972, delivering a crew that would stay for a record 84 days, clear to February, 1973! It would also be the first time that NASA would have to use both its Mission Control rooms (officially called the Mission Operations Control Rooms or MOCRs) to control two missions because Apollo 17 (I-1) would end the year with a mission launching on December 5, 1972. Launching on AS-515, the last of the original lot of Saturn Vs, the Apollo 17 CSM, named Sojourn by the crew, entered lunar polar orbit for a long-duration mapping mission. Unlike previous Apollo missions, this mission was flown with only two crew, the Mission Commander and Command Module Pilot. They arrived in polar orbit on December 7 and began full operations the next day. Another objective of the mission was to fully test the capabilities of the CSM, which was designed to have active operations up to 14 days. Previously, the longest missions had only stayed up for a maximum of 12 days. And so, from December 8 until December 16 they orbited the moon's poles, returning to Earth on the evening of December 19. Crew was Bruce McCandless and Anthony England.

We've now reached the end of the Apollo hardware that could have actually been used. Next time we'll start speculating about where new plans and technologies could have gone...

No comments:

Post a Comment